Not to worry

My good friend Doug Loneman called the other day with an invitation to head up to Hyalite Reservoir.

I was surprised to find the water level of the reservoir much lower than what I’d seen a few months earlier. A quick call this morning to the Bozeman Water Department assures me this is nothing to worry over. They bring water levels way down in the fall to save the dam from ice damage in the winter.

Still, it was an eerie place. The exposed ground, I was told, has only been under water since 1993, when the dam was enlarged. But the creeks still converged and then headed down toward Hyalite Canyon and it was easy to imagine the forest they once ran through, now sandy mud and stumps.

I’m sad for the forest now gone and at the same time glad for the water this dam provides me and the other people of the rapidly-growing population of Bozeman.

Then I think of the people in California, some of whom have been without running water for five months or more. And I remember that clean water has been in short supply in Africa and other parts of the world for a very long time.

The climate is changing. And water is more precious than oil. I hope we remember that in time.

New Music

Kenneth Fuchs is a great composer who wrote a piece that the Bozeman Symphony played at their last concert called Discover The Wild. Maestro Matthew Savery asked me to put together a slide show of Montana and Yellowstone landscapes to go along with this wonderful piece of music. Here’s what we came up with. The video lasts a little less than five minutes.

To The Dogs

For 33 years now, dogs from all over the U.S. and Canada have been coming to Helena for the Fall Roundup Cluster Dog Show. This is Grazie, a breed of Italian hunting dog called Spinone Italiano getting a bath after the first of four days of competition.

My friend Al Knauber, working for the Helena Independent Record, says more than 600 dogs entered the show. Al quotes Fred Thomas from Yakima, Wash., as saying, “Some of the best dogs in the country are here right now.”

My friend Al Knauber, working for the Helena Independent Record, says more than 600 dogs entered the show. Al quotes Fred Thomas from Yakima, Wash., as saying, “Some of the best dogs in the country are here right now.”

The dog show life can involve a lot of money and travel, Al goes on to write. Some owners hire handlers to show and travel with their dogs. Others have motor homes to travel with their dogs and are on the road up to 45 weekends a year.

Faith, a standard poodle from Houston, waits for a fresh round of hair spray.

Faith, a standard poodle from Houston, waits for a fresh round of hair spray.

Dragon Boats

Imagine this: You’re in a 46-foot canoe with 19 other weekend warriors paddling across Flathead Lake and there’s a crazy person in the bow beating on a drum and yelling at you to STROKE!

And you’re dressed funny.

That scene was played out time and again over the weekend at the annual Flathead Dragon Boat Festival at Flathead Lake Lodge in Bigfork.

Teams from Canada and the U.S. have been coming to Bigfork every year now since 2012 raising tens of thousands of dollars for local non-profits.

Bubble Ball

The other night, just before it snowed, some local teenagers wrapped themselves in plastic and air, then ran into each other — a lot.

It’s called Bubble Ball and started in Europe a few years ago. Here’s a video of people trying to play soccer wearing the things. The other night near the Emerson Cultural Center here in Bozeman, there was a soccer ball on the field, but it went largely ignored in favor of the fun of sending a friend flying.

A Foundry in Anaconda

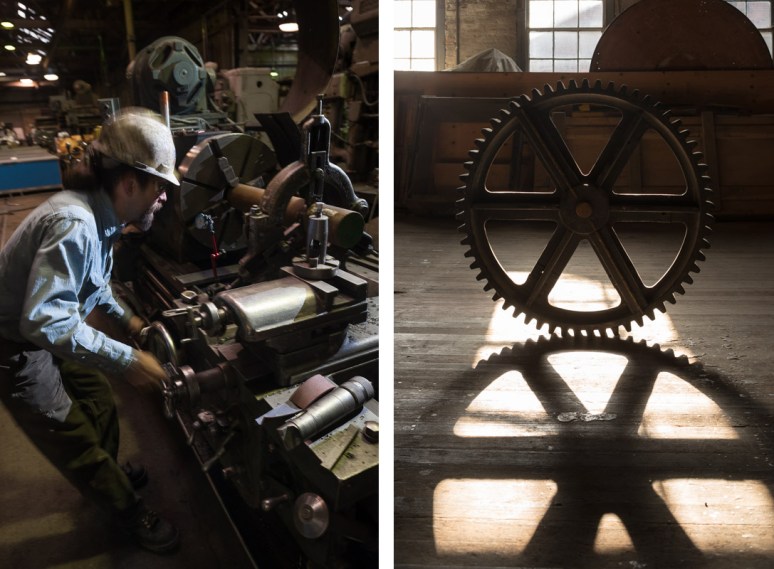

The new issue of Montana Quarterly is out and among other great stories is Jim Gransbery’s profile of the Anaconda Foundry Fabrication Company, in business since the 1890s. They do a lot of cool things at AFFCO, but nothing beats the pouring of metal ore into molds. The ore is so hot it looks like liquid fire.

Jim Liebetrau is president of AFFCO. He and two other men borrowed $600,000 in 1980 to purchased the foundry from the Atlantic Richfield Company, which had closed the foundry some weeks before. Liebetrau and his partners had just six employees.

Today, AFFCO employs more than 75 people in five departments: metal fabrication, where Allen Thorpe welds together a structural beam, a machine shop, a mobile construction component, and an industrial supply store in addition to the foundry.

There’s state-of-the-art equipment, sure, but a lot of the technology used at AFFCO has gone unchanged for a long time. Machinist Sterling Schmidt uses a lathe dating from the 1950s to form an idler shaft for a piece of machinery, and molds like this gear made from wood by hand shortly after Custer and his men lost the Battle of the Little Bighorn are still available if needed.

See these on my website.

#MontanaPhotojournalist #MontanaPhotographer.

Terry. Still.

The 2012 census counts just 596 residents of Terry, Mont., but it’s still the biggest dot in the 75 or so miles between Miles City and Glendive.

The Kempton Hotel is still open after more than 100 years. Russ Schwartz, whose grandmother worked at the Kempton around 1910, runs it with his wife, Linda. In 1991, having moved from Terry to Alaska, Schwartz says, “my mother called and said, ‘we’re buying the Kempton Hotel.’ What I didn’t know is that it was Linda and I that was buying it.”

Agriculture is still the driving force in Terry. “The two largest roots to the irrigated production we have on the Yellowstone River are the water itself, and fertilizer,” says Farmer’s Union Oil Company Manager Larry Keitner while Junior Fischer moves fertilizer pellets with a small tractor from bin to elevator to truck. Local farmers grow grains, hay and beans, Keitner says, using water from the Yellowstone to increase productivity and using chemicals to replenish nutrients in the soil.

Around Terry, ranchers still raise sheep, though more are turning to cows. “We’re an endangered species,” says Les Thomason of sheep ranchers. Once a mainstay of the area economy, Thomason says sheep have seen a steady decline since World War II. He guess that the 800 or so sheep he and his brother own constitute 90 percent of the Prairie County sheep stock.

And even though the Milwaukee Railroad line has been abandoned for decades, travelers can still use its old Calypso bridge to cross the Yellowstone and see the Terry Badlands.

Grit

Endurance.

To stick with something for six weeks is said to be all that’s needed to form a habit. These days, to have a job for 10 years is something of an achievement. To spend an entire lifetime on something is remarkable, and to spend multiple lifetimes in dogged determination is downright admirable.

Montana has been a state for 125 years this November. It was named a territory just a generation earlier. People have been ranching and farming this country for about as long, but we all know that times and ideas change, evolve. New generations are born with their own ambitions.

So when a ranch or farm stays in one family over a span of 10 decades or more, it’s to be celebrated.

The Montana Historical Society thinks so and in 2009, announced the creation of the Montana Centennial Farm and Ranch Program. So far, about 28 families have gone through the process of gaining official recognition as a Centennial Farm or Ranch. Here are three:

Benjamin Armstrong had nearly completed the coursework for an engineering degree from Iowa State College when he homestead a farm east of Geraldine in 1909. When his son Henry took over in 1965, The elder Armstrong had either built or drastically altered every piece of machinery except the tractor.

Henry Armstrong began working the farm with his dad after serving in the Marines in World War II. He’s in his mid-80s now and most of the day-to-day operations have passed on to his son, Stuart. Hope is that Stuart’s son, Alex, 24, will one day take over after he does a stint with the Marines like his grandfather.

Henry Armstrong walks past a 1929 Ford Model A he says was still in use in the 1980s. “How we got through the 30s,” Henry says, “we built it, we fixed it. We didn’t buy it.”.

Alan Armstrong is 24 years old and helps out with chores like welding on the Armstrong farm. But he’s just signed on for a stint the Marines, like his grandfather. So his future on the farm is uncertain.

Stuart Armstrong takes a hammer with him to fix a small problem with a combine.

Henry Armstrong pages through a journal his father kept in the year he homesteaded.

Near Sidney, John Mercer oversees the farm his grandfather Andrew Mercer homesteaded in 1901 along the Yellowstone River. A businessman, Andrew Mercer had been a prospector and owned and managed properties including a saloon in addition to the cattle, horses and wheat he sold. Andrew Mercer’s son, Russell, spent his life on the ranch and he and his wife, Mary, were active outside the family farm. Russell Mercer served in local government and Mary Mercer was an active advocate for the preservation of local history.

John Mercer is the sixth of Mary and Russell Mercer’s seven children. “I was doing construction in Denver,” he says, “and I came back in 1972 to save the place after Dad had a heart attack. I never knew anything about farming or ranching.”

He’s now semi-retired, he says, only managing the dry land farming at the place, leaving the irrigated fields to someone else.

John and Kathy Mercer pose in front of the house John’s grandfather Andrew Mercer built in 1906 at the age of 36, five years after homesteading the property.

John Mercer holds a picture of his mother.

People photograph what’s important to them, and John Mercer’s grandfather liked Belgian draft horses.

Laura Etta Smalley was a 25-year-old school teacher in Canada in 1910, prohibited from owning land because she was a single woman. That summer, she traveled into Montana, hired movers and a couple of wagons to carry a 12-by-16-foot cabin to a half-section of land just 10 miles south of the Canada border. When the movers left, she spent the night alone for the first time in her life. Her nearest neighbor was half a mile away.

More than a century later, her grandson Tom Bangs watches over that original half section, plus a few more, while his son Jeff eases into taking over the operation.

“It’s a pretty appealing life, really,” Tom says. “To be your own boss, to manage the land.”

Tom and Carol Bangs pose with their son Jeff and his wife, Katie. Carol, a native of Havre, is glad Jeff and Katie are there. “I value heritage,” she says. “Continuing on what your family started.”

A neighbor is a neighbor — even if half a mile or more separates the homes. The Bangs Farm is in a neighborhood known as “Minneota,” barely five miles south of the Canada border. “People are close, even though the distances are great,” says Carol Bangs.

Jeff Bangs, right, is 29 years old and in the process of taking over from his dad. Newly married, Jeff has land and equipment of his own while he eases into taking over the operation.

Jeff Bangs loads grain for winter wheat into a seed drill as evening comes on. As he begins his farming career he knows to expect the road to get rough. “You have to maximize the good times,” he says. “do as well as you can when you can and have some resources ready.”

Copyright

All images on this site ©Thomas Lee.-

Join 566 other subscribers

Thomas Lee True West

-

Recent Posts

Archives

- May 2018

- April 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- August 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- February 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- January 2016

- November 2015

- September 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

Categories

Meta