montana photograph Bird Tail

“This is an indigenous continental compass rose,” says historian and folklorist Nicholas Vrooman of Bird Tail Rock near St. Peter’s Mission in northern Montana. Vrooman says the rock marks the intersection of routes that lead to what we now call the Oregon coast, the Gulf of Mexico, Hudson Bay and the northern Rockies.

In 1878, colonial settlers built St. Peter’s Mission, very near the Bird Tail. Neighboring rancher Frank Crabtree says the church had fallen into disrepair when he began slowly restoring it 10 years ago.

Crabtree stands inside the church, where services are now held regularly.

Crabtree says the church organ was full of mice when he found it. It is now in working order.

The dove-tail joints on the corners of the mission were hand-hewn by an axe in 1878, says historian Nicholas Vrooman.

Other historical buildings at the site haven’t fared as well as the church. Two large stone school buildings were constructed in 1887 and 1892. By 1920, both had been abandoned and fallen victim to fire.

A cemetery remains, testament to the hard life many at the Mission endured. The cemetery contains the unmarked graves of many school children who died in the early 1900s.

“This is one of Montana’s absolute important structures, period,” says historian and folklorist Nicholas Vrooman in the shadow of St. Peter’s Mission north of Cascade.

See these on my website.

montana photograph Big Dry

Foresight is a handy thing — especially for a rancher in northeast Montana like Brent McRae. Foresight led McRae to put a few earthen dams on the ranch to try and hold on to what little precipitation came.

And, in spite of what seemed an awful lot of natural moisture last spring, it led him to install solar-powered pumps to fill a system of tubs strategically placed on his ranch for his cattle herd.

Good thing, too. Because for five months, they didn’t get a drop of rain.

But thanks to foresight, the McRaes and their Big Dry Angus Ranch made it through relatively well. This year will be a recovery year, McRae says. If it is a normal water year, things should be alright. But some of his neighbors operate too close to the edge, running a maximum amount of livestock on the land with little to no margin of error. Those are the neighbors who need a recovery year the most. If they don’t get one….

A close eye will be kept on the forecasts and weather data disseminated by the National Weather Service’s facility in nearby Glasgow, Mont. At the facility, people like Brian Burleson send up daily weather balloons 100,000 feet into the sky to measure temperature, wind, humidity and barometric pressure.

Water comes to the Milk River basin in northeast Montana from places besides the sky. Jeff Pattison stands in a length of pipe removed from the Saint Mary diversion project, which sends water bound for Hudson Bay from the Saint Mary River across a divide and into the Milk River basin.

Montana Departement of Natural Resource Conservation water planner Michael Downey says as much as 80 percent of the water in the Milk comes through those pipes from the Saint Mary. The Saint Mary water project is 100 years old and in desperate need of maintenance.

See these pictures on my website.

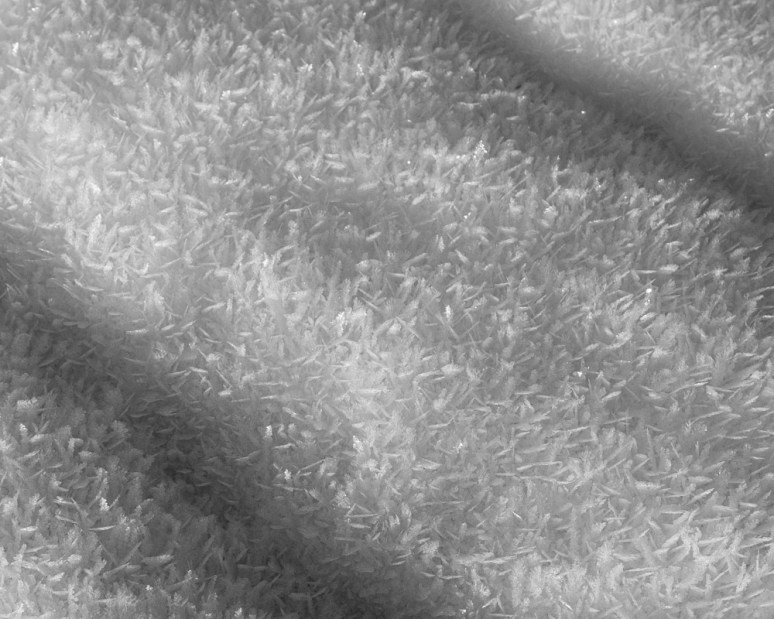

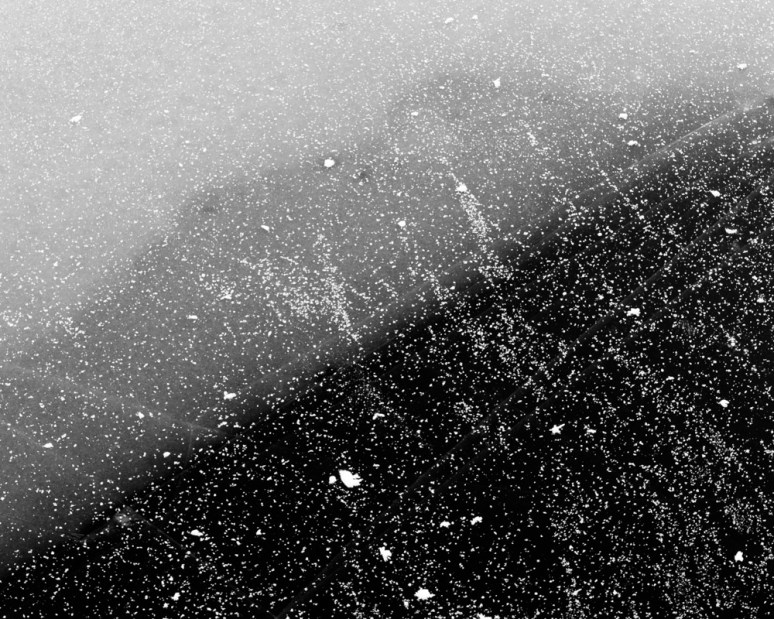

montana photograph Snow Grooming

The nights are long now in Bozeman, and we’ve had a lot of snow and cold, so we’re lucky to be able to boast a first-rate nordic ski trail system that’s within our city limits. That doesn’t come easy or cheap, but thanks to a lot of effort and a willingness to work through subzero nights on a regular basis, it happens.

Bob Seibert started voluntarily grooming a nordic trail near Bozeman when he moved here in 2005 with a snowmobile pulling a track setter. In his final winter season, 2016-17, he drove the Bridger Ski Foundation’s PistenBully grooming machine worth in excess of $100,000.

Kyle Marvinney moved to Bozeman from Maine to take over the grooming responsibilities from Seibert. Marvinney checks the fluids of the PistenBully before each use — part of a careful maintenance program designed to make the expensive machine last as long as possible.

Even at night, groomers can encounter skiers on the trails. That’s bad for grooming, Seibert says, because the snow needs several undisturbed, un-skied hours to set up properly for optimal ski conditions.

Kyle Marvinney, left, and Bob Seibert.

See these on my website.

montana photograph 2017

Trouble

Treachery

Evidence

Lurking

Fear

Vertigo

Uncertainty

Dizzy

Confusion

Careful

Trepid

Overwhelm

Out of the Darkness, Light

montana photograph Livingston

The Huffington Post teamed up with Scott McMillion and Montana Quarterly magazine for a piece on Livingston, Montana, a few weeks ago and I was glad to get the assignment to illustrate the story.

The story, like Livingston, centers on the railroad. Livingston was founded by the Northern Pacific railroad in the 1880s and made it a service stop for its engines. Livingston prospered. And then the railroad pulled out, leaving behind a superfund cleanup site a century later.

Bill Phillips, now 77, was a machinist for the railroad. He lives along the banks of the Yellowstone River east of town now and remembers oil and chemicals being just dumped onto the ground at the engine yards in Livingston.

I found a deer grazing near the superfund cleanup site.

Doug Thompson remembers working in the paint shop during his 34 years with the railroad. Thompson, now 71 and retired, lives a short walk away from the plant where workers were told to use a pressure hose to spray stripped paint and the stripping chemicals right out the door and onto the ground.

Dick Murphy now lives in a cabin built in 1883 along Mission Creek east of Livingston with his dog, Annie. Murphy says he worked for the railroad right out of high school and saw frequent large spills of diesel fuel.

Murphy, Thompson and Phillips were a few who started to speak out about the problems in the 1970s. They were branded trouble makers.

The story goes on to describe the cleanup efforts that are still ongoing, now more than 30 years later, as well as the lasting impacts of the pollution.

And the story describes Livingston, where we lived for three years in the late 1990s when we first moved to Montana. It’s a place that embraces its history, presenting itself as an authentic small town in the American West, with amenities to attract tourists to the world-class fishing nearby and the topography of Yellowstone National Park, only a short drive to the south.

You can see the pictures on my website. And you can read the full story here.

montana photograph Headframe Spirits

I love Butte, Montana. It’s genuine and it’s honestly humble. Butte owns its mining past, good and bad, and it moves forward with friendly grace.

Courtney and John McKee are examples of that. In 2012, they started Headframe Spirits, named for the structures that mark the mine shafts scattered inside the Butte city limits. They distill spirits and also make the stills.

Headframe Spirits took over a building that used to be a Buick dealership in uptown Butte, Montana.

Mike Stoltz welds a stainless steel patch onto a tank at the Headframe Spirits distillery in Butte, Montana.

John McKee says he founded the company after a job distilling biodiesel fuel ended. He says his continuous column stills are more than twice as efficient as the old pot stills.

Every bottle of whiskey sold by Headframe Spirits gets a hand-written note.

Bartender Jessica Tutty pours a glass of Neversweat bourbon. Each whiskey produced by Headframe Spirits is named for a mine in Butte, Montana.

See these pictures on my website here.

montana photograph Shear Pleasure

Shannon Kahler isn’t your typical sheep shearer. While most operations are geared to shear hundreds, perhaps thousands of sheep at a time, Shannon caters to the small hobby farmer with just a handful of sheep. She spends double the amount of time per sheep as the commercial shearers, says she’s offering the animals a “spa day.”

The sheep can outweigh her by 100 pounds or more, so she brings along her husband, Robert, when she can.

Shearing is good animal husbandry. For one thing, it shows wounds like this one, likely sustained in an unpleasant encounter with barbed wire, that can then be treated. For another, if left unshorn, the weight of the wool can tear the animal’s skin.

See these on my website here.

montana photograph Time

These are contentious times in our state, our nation and our world. There is a lot of fear out there and that fear is really loud.

Living here, we’re lucky because it’s easy to go somewhere and be quiet with rocks, trees and water. For me there’s comfort there. I see patience, endurance, trust.

They say time heals all wounds. I can see how that might be true. And I hope to God we start healing quickly, because the wounds only seem to be getting deeper.

montana photograph Lasers

Sure, Montana has it’s requisite of mountains, wildlife and people who are connected with the land, but we’ve got tech too.

Zack Cole, director of scientific materials at FLIR Systems, Inc., in Bozeman, peers through a garnet crystal used to build high power laser systems for cutting and welding sheet metal in automotive and heavy equipment manufacturing.

Light travels through a crystal to illuminate the materials from which it was made: a raw powder of aluminum oxide and lutetium oxide, according to Cole, which are then melted into a liquid and re-solidified at a temperature nearing 4,000 degrees Fahrenheit.

At the Tech Park Facility of FLIR Systems, Inc., laser light travels into a crystal under the watch of Zack Cole. Cole says the process is a way to find imperfections in the crystal.

Crystals made to be used in lasers by FLIR Systems, Inc., stand on a lab table. Cole says the different colors are indicative of different materials used in the making of the crystals and also the differing potential uses of the crystals, which include detection of X-rays, cutting and welding sheet metal and use in space applications like satellites, Mars rovers and International Space Station docking facilities.

See these and more on my website.

Copyright

All images on this site ©Thomas Lee.-

Join 566 other subscribers

Thomas Lee True West

-

Recent Posts

Archives

- May 2018

- April 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- August 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- February 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- January 2016

- November 2015

- September 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

Categories

Meta